- Home

- Virginia Bergin

Storm Page 2

Storm Read online

Page 2

So I suppose it was probably me that let the sheep out, the one that had nearly killed me.

(See what I did there? I blame it on the sheep.)

First farm I came to, I tried to go in. I wasn’t even thinking “.” I was thinking “.” They hurt so bad, and they wouldn’t stop weeping, and I was scared that if I didn’t find something to wash them with immediately, I wouldn’t be able to see at all.

A scrawny sheepdog came out into the yard and barked at me.

I know the type; they won’t attack you. They’re just telling you: this is not your house.

“You good girl,” I said—or tried to. Since the picture thoughts had taken over, I didn’t even speak to myself out loud anymore, and even though I had just shouted at my own shadow, my voice came out all broken up and ragged and weird.

“Good girl,” I tried again, and me and the dog, whose bark also seemed a little strained and peculiar (it could just have been the shock of seeing someone), both stared miserably at each other—except it was getting harder and harder by the second to stare at anything.

“Please…” I begged, but no way was the good girl—who might have been a boy—going to let me in that house.

I drove back home on a tractor. The good girl wasn’t too sure about that either, but she gave me the benefit of the doubt. She even followed me, as if she thought it might be time to go to work or something…but that skinny girl, she couldn’t keep up. She barked at me to stop and wait for her, but I couldn’t. I didn’t. I didn’t even want to hear that bark.

Dogs, animals…people…they’ll break your heart.

I zoomed home on that tractor, so high up on that driver’s seat that over the banks and hedgerows, I could make out blurry fields. I didn’t feel hemmed in and spooked like I normally do, not knowing what might be around the next bend. Even if we smacked into a wall, the wall would come off worse.

Blind Farmer Ruby, rollin’ along. And whatever I might have rolled over, I didn’t see it. I just felt the occasional bump. There is some terrible stuff lying about these days.

I made myself dump the tractor at the end of our road because I was worried if I went any farther, it’d get stuck between the lines of cars and I’d lose an exit route. I dumped it and I ran, my eyes so blind, my hands so shaky I could hardly get the key in the lock.

I stepped inside the house and called, “Dad?!”

Yeah. That’d be the last time.

I slurped cola and washed my eyes with the tiny bit of water I had left. Couldn’t even see anything much in the mirror, just a blurry version of my face that looked like it felt: puffy, red, and busted. I squinted at one particular mark on my cheek. Double circles. Matched my watches. (I wore four: two digital, two wind up—don’t ask.) Perfect imprints of one wrist’s worth on my cheek. But it was my eyes that looked weirdest.

“Love! You look like Joe Bugner,” Grandma Hollis once said to me, at the time when I’d first been told my mom and dad were splitting up and I’d cried so much my eyes puffed up.

I didn’t know who Joe Bugner was; I still don’t. All I ever knew was that he was a boxer.

Yeah, I looked like I’d been in a fight.

There were decisions to be made. I knew that, but all I wanted to do was go to bed. No idea what the time was, no idea what day it was. No idea what I was going to do. The only thing I did know was that I needed to do something. But first, there would be sleep.

It was a very long, bad, and snore-y sleep. It was snore-y because my nose was full of blood. I couldn’t breathe properly, and eventually I worked out this was how come I kept waking myself up—waking myself up but not really waking up—thinking the ghost girl was in the room, speaking some growly shadow language at me. The last time I snored myself awake, I picked out dried blood from my nose (too much information?). It hurt a lot. I guzzled cola and went back to sleep and dreamed the ghost girl in the mist had become a death angel, coming toward me as church bells tolled.

But I wasn’t dreaming.

When I woke up, the church bells were close and clanky, and went on and on in a random, awful, dong-clank-dong-dong way—not like the fancy tunes the proper bell ringers used to do. At first I thought I hadn’t woken up. I’d had plenty of dreams like that—nightmares—when I’d thought I’d woken but I hadn’t, and the nightmare would go on and I’d think it was really happening, and then if I did wake up for real, it was no good going back to sleep because the whole thing was lurking in my Planet Ruby head waiting to start over. What you had to do was wake yourself up good and proper and read something or listen to some music (the boom box and the cassette tape of brass band music belonging to my dead neighbor, Mr. Fitch, had been upgraded to a CD player and a vast, jumbled heap of discs and cases) and no matter how much you wanted to go back to sleep, you just couldn’t let yourself do it until the nightmare had been battled back into the part of your brain it had snuck out from and could only rattle at the crummy lock on the door.

But those bells, they didn’t stop, not even when I got up—WAH! MY BODY HURT! WHOA! I HAD THE MOST MASSIVE DIZZY FIT!—and picked my way around the house slugging cola (I was SO thirsty!), shivering because I felt weirdly, seriously cold and because I was SCARED OUT OF MY MIND.

I must have been asleep all day and all night, because it was day again—middle of, judging from the light, which I had to do because my watches all told different, blurry stories—but at least I could see them. At least I could see. That was the only comfort in the situation because I felt this most incredible panic…a different kind completely to the one I had felt up on the moor, different again to the one I had felt thinking I was going blind and how would I get back home. It was the panic of another human being coming. It was the panic of choice.

Those church bells? They’d only clank and dong like that if a person—a real, live, actual person was ringing them.

It was a panic I couldn’t even stall by doing something normal, like getting dressed or something, because I was already dressed. Ha! I even had my rubber boots and raincoat on still.

All I could do was stand at the front door, slugging cola and going, “Oh—”

Mom, I can’t put any more pretty butterflies where swear words should go. I’ll put a new thing: .

It is what killed you. It is the thing in the rain. There is no worse thing. So I will put this thing instead. And I will fill it with hate.

So yeah, I stood at the front door going, “Oh , oh , oh ,” because I was too scared to go out.

You know that stuff you learned at school and from your parents when you were tiny? That stuff about “stranger danger”? Well, really, right up until the apocalypse, I’d sort of thought, Yeah, right, because most people you ever met were OK, really, and some of them were really nice. (And anyway, how would anyone ever meet anyone if everyone was scared of strangers? All you’d ever know was your own family.) But since the apocalypse? Strangers make me really nervous. I’ve seen all kinds of random freaking out and nastiness. (I’ve also seen all kinds of weirdness: e.g., opened the door to a discount warehouse near here and saw a butt-naked man lying on a pile of sheepskin rugs singing.) (I closed the door and left.) (Quickly.) If some stranger came now, if someone found out where I was, I couldn’t run, could I? How could I go when my dad said he was coming back?

It’s that, I think, more than anything, that made my default setting LIE LOW. Anytime I went to a place to check it out for water or food and I even thought for one second that someone had been there, I left. (Quickly.) Even if there was a whole Aladdin’s cave of stuff right in front of me and no naked man singing, if I saw something—a spilled thing, crumbs, mold even—that looked fresh or even halfway fresh (know your molds!) or I smelled something recent-ish and human, I’d just leave. (Quickly.) That’s how it got. That’s how sharp I could be when I wasn’t zombied out with misery.

The church bells stopped ringing.

/> “Oh .”

I said it out loud. I think I said it out loud. Seemed to me my own voice boomed out in the silence louder than any bell. It was, perhaps, the most complicated “Oh ” there has ever been. On the one hand, relief swept over me—because I could maybe think that it was over, so chillax, Ruby, go back to sleep (as if!)… On the other hand…someone else was in town. Someone who really wanted people to know they were around. A crazy someone-anyone setting a trap—or a desperate someone. Or. Or. Or.

“!” I boomed.

I opened the door.

The sky looked OK—for now—some kind of cirrocumulus stratiformis thing going on = basically a high-level mess of clouds that could turn into a whole bunch of nastier ones…but not yet.

I’d run out of all excuses other than fear.

In my family, unless someone was getting married, we went to church once a year—at Christmas, because my mom liked the carols. For me, this was going to be the second time this year, if Salisbury Cathedral counts as a church. That’s the apocalypse for you: makes you go places you wouldn’t normally go, do things you wouldn’t normally do. It’s just great that way, isn’t it?

I prowled down into the town, the raincoat rustling way too much for my liking. I prowled cautiously, listening for every and any sound…but it was difficult to hear any sound that wasn’t CLANG DONG CLANG because that CLANG DONG CLANG started up again when I was halfway there.

When the only sound disturbance in your world, for ages, has been yourself or the wind or the rain, any other sort of noise is REALLY FRIGHTENING. Not that many times but often enough for me to be pretty sure I wasn’t dreaming, I’d heard planes. I’d even heard other cars a few times. But this?

It was the loudest thing I’d heard in months (that wasn’t coming out of a CD player in a car). Louder even than the WTCH-UH, WTCH-UH thump of my own heart—which was hammering so hard it felt like I could hear it.

I snuck up to the church. I hid behind a grave. The bells stopped.

WTCH-UH, WTCH-UH. My body detected nervous sweat pouring from my armpits. WTCH-UH, WTCH-UH, WTCH—HUH?!

Someone came out of the church.

I suppose I did just pop up from behind a gravestone. I suppose it might have been a bit sudden. Anyway, whatever it was, Saskia screamed.

“Saskia?!” my ragged, broken voice squealed out like a strangled thing.

She just stood there, a frozen human explosion of fright. It seemed a little over-the-top if you ask me. (Considering, before the rain fell, we’d seen each other every day at school and every weekend too.)

“Sask?!” Erm, so I suppose my voice was a bit grunty and cavewoman-like. It definitely sounded pretty weird.

“Ruby?!” she whispered, like she really wasn’t sure about it when—Hey?! Hello! Of course it was ME. OF COURSE IT WAS ME!

“Oh my !” She gasped. “What HAPPENED to you?!”

I wasn’t really listening. I felt this massive…this massive…I want to say it was totally, like, some kind of surge of love and human compassion (even though she looked as annoyingly fresh and perky as the last time I’d seen her, safe inside the army base with all the useful people, and—allegedly and apparently—shacked up with Darius “Don’t Ever Want to Think about Him” Spratt). The truth is, when I realized it was her, just her and not random, scary someone-anyone other people, I felt this MASSIVE SURGE OF RELIEF…which sort of became this massive surge of…oh, I don’t even know what, but before she had time to dodge out of the way, I sort of lunged forward and grabbed her. I hugged her.

She gasped again. “You scared the hell out of me!”

I think I might have tried to grunt something back.

“I didn’t know if you’d be here! I didn’t know where you lived! I didn’t know how to find you!” she cried.

And then there was just this…we hung on to one another, rocking and swaying and trying to hold the world still in the middle of a graveyard. A graveyard full of people who’d died when they should have died—or maybe even tragically, but with people alive to comfort each other, people alive to share the pain and the sweetness of remembering.

We had none of that.

We had only each other.

It took a little while to really get your head around that. It took a lot less time for us both to regret it.

CHAPTER THREE

“!” Saskia choked, gagging, when I opened the front door.

“!” she shouted and made a terrible retching noise.

I was somewhat offended, but also I somewhat got it because I also somewhat knew what she meant. How my family smelled. So I found this pot of menthol rub I had for the times it got to me too (total CSI job) and Sask smeared some under her nose and did this oh-so-obvious “bracing myself here” thing, then came inside.

“Oh my ,” she murmured from behind the hand that was over her mouth.

It took a visitor to make me see the house for what it was. The smell was one thing and could not be helped. Everything else, I realized, seeing it through Saskia’s eyes, could, possibly, be helped.

Everything else was down to me.

OK, so I hadn’t cleaned up much. Household hygiene wasn’t a huge priority on Planet Ruby. Also, for convenience, activities that would normally be assigned to designated rooms pretty much all took place in one room. The sitting room—apart from still being my sitting room, where I’d spend hours, um, sitting—was also my dining room, my field kitchen (got me a little camping stove in there), and my bedroom. Also my hair and beauty parlor!

You could just make out a sleeping spot in the corner, littered with empty packets of painkillers and cola cans, but the whole of the rest of the room was…OK, so it was a mess, but there was a way through it, all right? You just had to be careful about not slipping on the treacherous slopes of the CD mountain, but that was preferable to wading through the clothes, books, and makeup swamp because—OK, so there was a lot of food-related debris involved.

But I mean, most of the cans and bottles and jars and stuff were more or less empty and the whole fly situation had gotten a whole lot better just lately. And it was hardly my fault that there was no more electricity, so that waterfalls of wax had cascaded from the candles that stood on every flat surface. The TV actually looked quite pretty, in an arty sort of way, but it remained an unfinished work, as I’d eased off on the candle burning after the coffee table fire.

Unfortunately, the sitting room was also my bathroom. Vast flocks of used wet wipes and, um, tissues frolicked in the central swamp area. No sanitary napkins, though, being as how I hadn’t actually had a period since the rain fell. (I’m assuming that when my body realized the only reproductive opportunity left was Darius Spratt, subnerd of subnerds, it went on strike.)

Ah. Then there were the bathroom buckets. Defensive measure. No use trying to explain to Sask that a full bathroom bucket had once saved my life. Hadn’t I chucked one into the face of a someone-anyone scary man? There was a bleach-frothing, half-disintegrated poo floating shamelessly in the closest bathroom bucket. I tried to nudge the bucket out of the way…

“Oh my .” She choked, as a fresh waft of stink added itself to…

So my house was a stinking pit, all right?

“Why don’t we go through to the kitchen?” I suggested, knowing it wouldn’t be any better but that at least no poos lurked there.

At least I thought not; on Planet Ruby anything was possible.

Saskia stumbled her way through.

She looked frightened. I think it was the writing on the walls that did it.

“It’s in case my dad comes,” I said.

She just looked at me.

“So he knows where I’ve gone…”

Looking at it through Saskia’s eyes, the only place my dad would think I’d gone was Nutsville. Every time I’d left the house, I’d written when I was going (day, dat

e, time), where I was going (or roughly, if I wasn’t sure), and when I’d be back. EVERY TIME. But the messages, which had started out all neat and orderly and efficient, had gotten a little vague and scrawly.

First the date went—what did it matter?—then I dropped the days—too much hassle—then the time became approximate. Things like “10:57 a.m.” had become “morn.” You could see the moment—some time back now—when I’d realized this was happening, which coincided with the whole watch/clock panic.

I haven’t really explained that, have I? I am only going to explain it now so you don’t join Saskia in thinking I’d lost it. I mean, obviously I had lost it, but there had definitely been moments when I hadn’t, and the whole clock/watch thing is a perfect example. The very first time I realized I was losing track of time, I had dealt with it. That’s when the first digital watch and the wind up (backup) happened. Then I forgot to wind the watch, and the digital one fogged up after a hair-washing session in the camp, so I went into overdrive. Basically, I’d ticked (two wind ups), and the house had ticked (Ruby the clock keeper), although getting all these watches and clocks to agree with each other was exhausting. (I might have given up a bit.) (Though some of them were still hanging on in there, ticking away.)

Anyhow, after the clock/watch panic, the messages on the wall pulled themselves together for a bit before they slumped back into their old bad habits. The most recent stuff on the door (I’d run out of wall and cupboard space)…it didn’t really look like human handwriting at all.

“Would you like a cup of tea?” I asked her.

“Ruby…oh my …” she breathed (not heavily). She actually had tears in her eyes. (Though it could have been the menthol rub; it can really make your eyes water.)

Now, see, here’s a funny thing. You’d think, wouldn’t you, that this could be some kind of lovely moment when I realize that at last a friend has come (well, not a friend, but at least a someone I know), and that she is distressed to see my situation. Let me tell you, it got right on my nerves. Instantly. I felt like she had NO RIGHT to stand in that kitchen dripping with pity. A million times I had felt howling pity for myself, but hers I did not want. Just one look at her was enough to tell you that life on Planet Saskia had been just fine and—

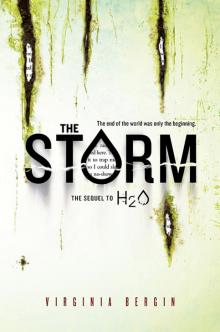

H2O

H2O The Rain

The Rain The XY

The XY Storm

Storm Who Runs the World?

Who Runs the World?